by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Sep 12, 2025 | Gardening Tips and Tricks, Western Container Gardening With Flowers

I used to think that once you planted your flowerpots, that was it. Your flower babies were in there for the long haul.

But I’ve come to appreciate that you can swap out the flowers in your pots.

It’s like changing your wardrobe for the seasons.

If you want to change the flowers in your flowerpots, you can — especially in the late summer to early fall. You can change just one flower. Or, you can change them all.

Why would you change the flowers in your pots?

There are all kinds of reasons.

Let’s say:

- You want to spice up your flowerpots for a new season — like transitioning from spring to summer, or summer to fall.

- You have an empty gap in your pots. Some of your flowers didn’t fill in quite like you thought they would.

- You’d like to add in more color.

- You have perennials planted in your flowerpots. They’re done blooming for the season. (Perennials are the flowers that can come back each year, but often bloom for a short amount of time.)

- There’s a flower in your flowerpot that doesn’t look so good or it may have died. (No judgment! It happens.)

Late summer to early fall can be a good time to add in new flowers

As we transition to fall, one of my favorite flowers to add to my flowerpots is Black Eyed Susan.

(This plant goes by many names, including Rudbeckia and Gloriosa Daisy.)

You can find it in a lot of pretty colors, as you can see below.

Black Eyed Susans give flowerpots a bright pop of color. They can bloom for a long time.

Best of all, these flowers feel like fall — like a Sunday drive to go leaf peepin’ or the sweet smell of mulled apple cider after a trip to the pumpkin patch.

Give your flowerpots a fresh look for fall

If you’d like to freshen up your flowerpots for fall, you can pop in flowers like…

- Black-Eyed Susans (aka, Gloriosa Daisies)

- Mums

- Ornamental Cabbage

- Ornamental Kale

- Pansies

- Violas

You can see some examples below.

Helpful tips if you change the flowers in your flowerpots

1) Keep your new flowers well-watered

Flowers tend to like A LOT of water when they’re newly planted in flowerpots, especially in our late-summer heat.

You may need to water your pots more than you have been doing.

Keep your eye on your newly-planted flowers. They can get droopy or crispy quickly.

2) Keep your eye on temperatures

Many fall flowers are “cool season” flowers.

They’re happiest when our days and nights start to cool down.

This means you may want to hold off on planting flowers like Pansies, Violas and Ornamental Cabbage until temperatures start to cool off. For example, Pansies tend to be in their happy place when daytime temps are in the upper 50s and 60s, and nighttime temps are in the 40s.

3) Look for plants that have new buds on them (meaning all the flowers haven’t opened yet)

This is one way to ensure that you’ll get longer-lasting color from your new flowers.

If you’d like to see photos of what I’m talking about, check out these 3 simple tips to pick fall flowers that bloom longer.

Related topics that may interest you:

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Jun 20, 2025 | Flower Garden Basics

Colorado has 5 plant hardiness zones: 7, 6, 5, 4 and 3.

If you’re new to plant hardiness zones, they tell you whether your flower plants are likely to survive the coldest winter temperatures that are expected in your area and come back next year.

(For the full scoop on hardiness zones, check out: What is a plant hardiness zone? And why they matter.)

So, what plant hardiness zone is your Colorado garden? It depends on where you live, as you can see in the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map for Colorado below. Scroll down this page for specifics.

Areas with warmer winters have higher zone numbers. They’re in green. Areas with colder winters have lower zone numbers. They’re in purple and pink.

Let’s look at plant hardiness zones in Colorado in broad strokes:

- If you live in the hottest parts of Colorado — like the southwest corner and parts of the Grand Junction area — you’re likely in plant hardiness zone 7. Surrounding areas are in zone 6.

- Much of the Front Range is in zone 5.

- But if you live in an urban corridor — like parts of Denver, Aurora, Boulder and Fort Collins, as well as parts of Colorado Springs — you’re likely in zone 6a. Buildings and concrete can heat things up. Much of Pueblo is in zone 6 too.

- At higher elevations, like up in the mountains, your plants often need to be able to withstand colder winter temperatures. (For every 1000 feet you go up in elevation in Colorado, temperatures drop about 3 to 4 degrees.) Your garden will likely have a lower plant hardiness zone number. The majority of mountain towns are in zone 4. Some are in zone 5 and a few are in zone 3.

There are exceptions to the “it gets colder as you go higher” guideline.

For example, if you live on a valley floor in Colorado, your garden can be up to 10-degrees COLDER than your neighbors on nearby hillsides or mountainsides.

Cold air slides down the slopes and settles on valley floors at night.

Another exception…

If you live on a north-facing slope, your garden may be a lot cooler and damper than the dry, heat-gathering gardens on south- and western-facing slopes.

And one more exception…

It’s possible to create “microclimates” in your garden that are warmer than the surrounding area. For example, you could include large boulders in your garden. Boulders and large rocks can radiate heat to surrounding plants and help block winds. Often times, flowers planted along the south and western sides of buildings or rock walls can receive more heat too.

Also worth noting… the USDA released an updated zone map for 2024.

With the new release, some parts of Colorado grew “warmer” in plant hardiness zones.

For example, my garden in the Front Range went from a 5b zone to a 6a zone. This means the lowest coldest temperatures that are expected where I live went from -15 degrees below zero to -10 degrees below zero.

But here’s something to consider. While our summer temperatures are getting hotter, it’s still possible that we can get a really cold winter. (Brutally cold winters just may not be as frequent.) Where I live, we’ve had winter temperatures reaching -15 degrees below zero and -17 degrees below zero in two of the last five years. Technically, these are still zone 5 temperatures. So, even though the USDA map says I’m 6a, I’m going to continue to think of my garden as zone 5. That way, I’m buying plants that are more likely to survive.

What’s the takeaway? Your local surroundings play a role.

The zone you’ll get from the USDA may not accurately reflect what’s going on in your individual garden in Colorado. You may want to adjust down a zone (for colder conditions) or up a zone (for warmer conditions). Just keep this in mind as you get your Colorado hardiness zone below!

To get the Colorado plant hardiness zone for your garden:

Click to the USDA website here and enter your zip code >>

Related tips that may interest you:

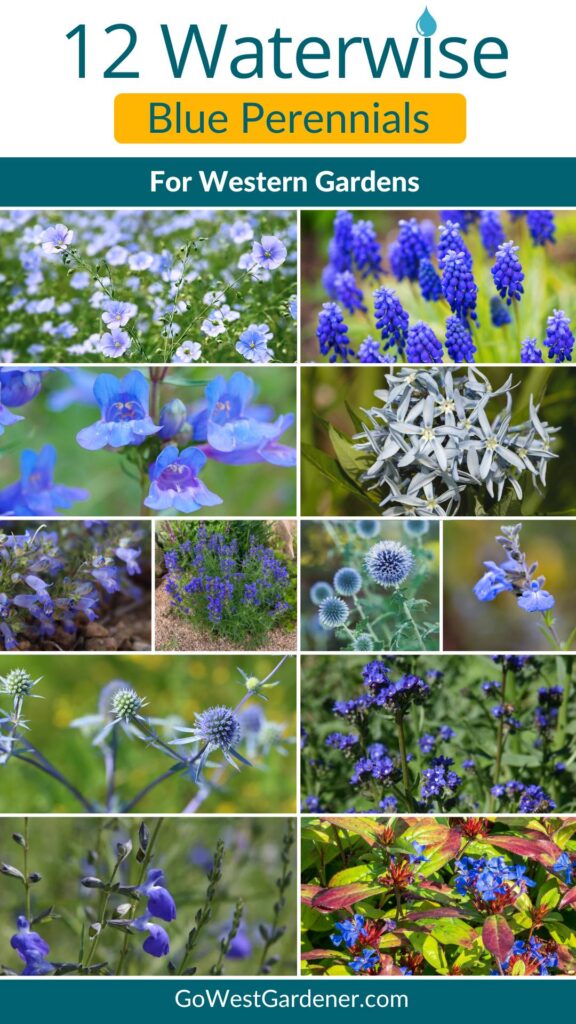

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Sep 12, 2025 | Best Flowers for Colorado, Utah & Similar States, In-ground garden, Waterwise Gardening in the Intermountain West

Confession: I love blue flowers. There’s something about them that makes my heart sing. In Colorado, Utah, and similar states, we’re lucky to have a variety of waterwise, blue flowers available to us as perennials (plants that return for multiple years).

Here are 12 waterwise perennials with blue flowers to get you started. These drought-tolerant beauties can handle our tricky, western conditions—from low precipitation to summer heat.

SPRING BLOOMERS

Blue flax (Linum lewisii)

Zones 4-9

Blue flax is a “What’s that?” plant… as in, your neighbors will stop and ask about this drought-tolerant perennial. It has airy, ferny leaves and charming, blue flowers in May and June. The flowers can be pale blue, powder blue or sky blue. Flowers open in the morning and close in the evening.

Blue flax can reseed heavily if you let it go to seed—like a fairy godmother tossing pixie dust—so think about where you plant it. It prefers a lot of sunlight and well-drained soils.

If you’d like a blue flax that’s native to Colorado, Utah and Wyoming, Linum lewisii is the easiest one to find in stores and at plant exchanges. The Colorado State University Extension says it can grow at elevations up to 9,500 feet! If you aren’t picky on native origin, there are European blue flaxes available too, such as Linum perenne (zones 4b-8) and Linum narbonense (Zones 5-8).

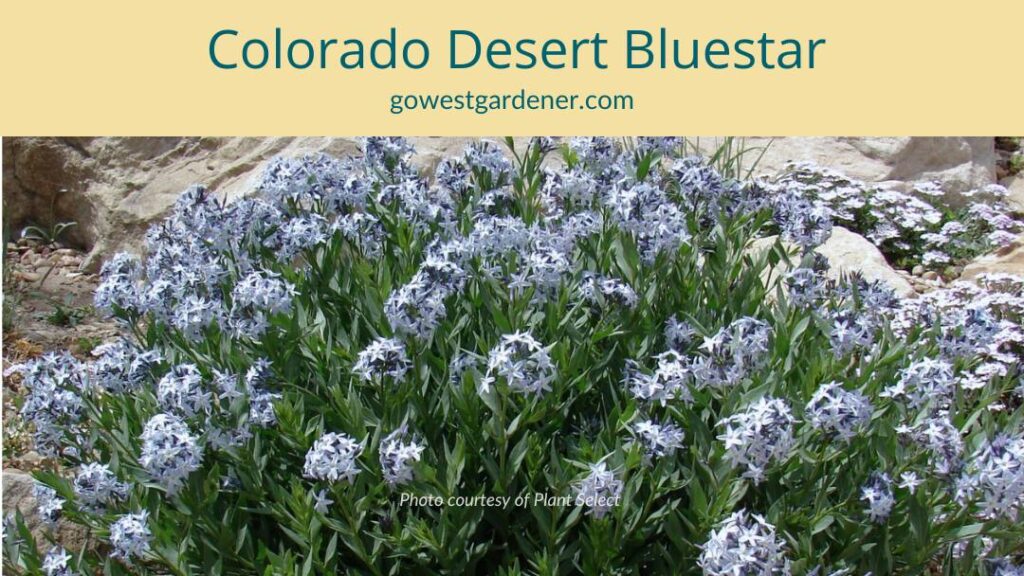

Colorado desert bluestar (Amsonia jonesii)

Zones 4-9

Colorado desert bluestar has pale-blue flowers that look like stars. It blooms in April and May. During autumn, its leaves turn yellow, offering a splash of fall color.

Colorado desert bluestar thrives in hot, sunny and dry locations. It’s very waterwise. Worth noting, this perennial can take several years to grow in size, so consider buying a bigger plant to get started. Otherwise, plan on being patient for a few years. (It’s worth the wait.)

This perennial can be a hard one to find, so if you see it at the garden center or a plant exchange, snag it!

Blue penstemons / beardtongues (Penstemon)

Penstemons (aka, beardtongues) typically put on a colorful show in late spring and early summer gardens in the West. They thrive in hot and sunny locations. They can keep their green foliage through most of the year, including winter. These plants attract hummingbirds and bees.

There are a number of penstemons that have blue flowers, including:

- Grand Mesa penstemon (Penstemon mensarum) — native to Colorado and Utah (zones 3-9)

- Blue Mist penstemon (Penstemon virens) — native to Colorado and Wyoming (zones 4-8)

- Electric Blue penstemon (Penstemon heterophyllus ‘Electric Blue’) — a selection of a California native penstemon (zones 5-9)

- WAGGON WHEEL® bluemat penstemon (Penstemon caespitosus ‘P022S’) — a selection of a low-growing penstemon that’s native to Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and Arizona (zones 4-7)

All of the penstemons listed above thrive in waterwise gardens.

Muscari / grape hyacinth (Muscari armeniacum)

Zones 4-9

Muscari (aka, grape hyacinth) has deep-blue flowers that bloom in the middle of spring. It grows from a bulb you plant in the fall. It naturalizes easily in western gardens, so it can spread and come back year after year. Muscari is drought tolerant, making it a good addition to waterwise gardens. Plant it en masse for a big splash of color.

Muscari offers bees an early source of food before many other plants have started blooming.

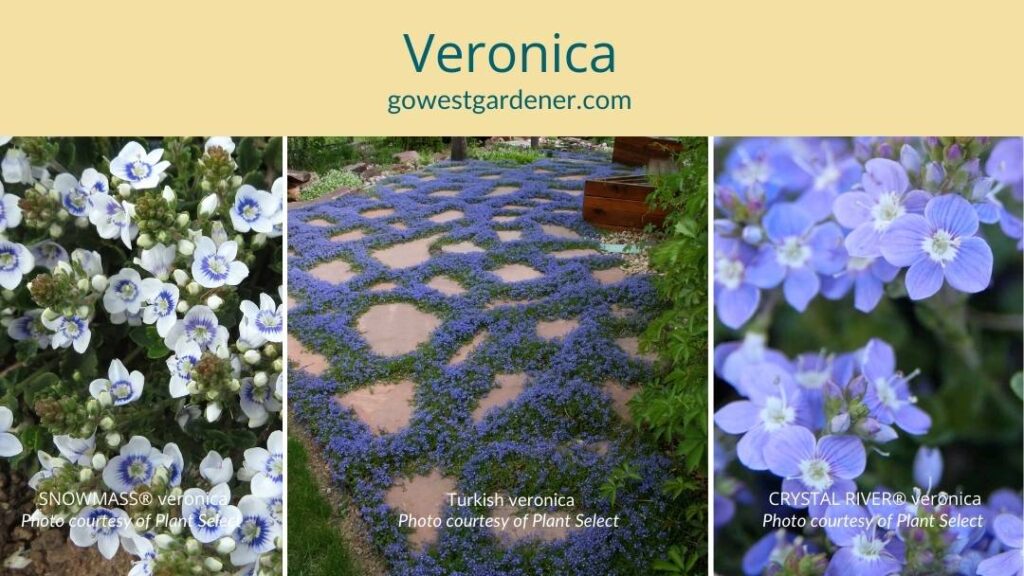

Turkish veronica (Veronica liwanensis)

Zones 3-10

Turkish veronica is a low-growing groundcover. It gets tiny, blue flowers in May. Plant it among pavers and walkways for a pretty look or along the fronts of your garden beds.

Turkish veronica will grow in partly shady locations, as well as in sunny locations. (You’ll get more flowers in the sun.) The leaves are evergreen, meaning they typically stay green throughout the year, including winter. This plant takes low to average water.

There are variations of this perennial that have blue flowers as well. For example, CRYSTAL RIVER® veronica has lilac-blue flowers with a white center (zones 3-7), and SNOWMASS® blue-eyed veronica has white petals with blue centers (zones 3-10).

SUMMER BLOOMERS

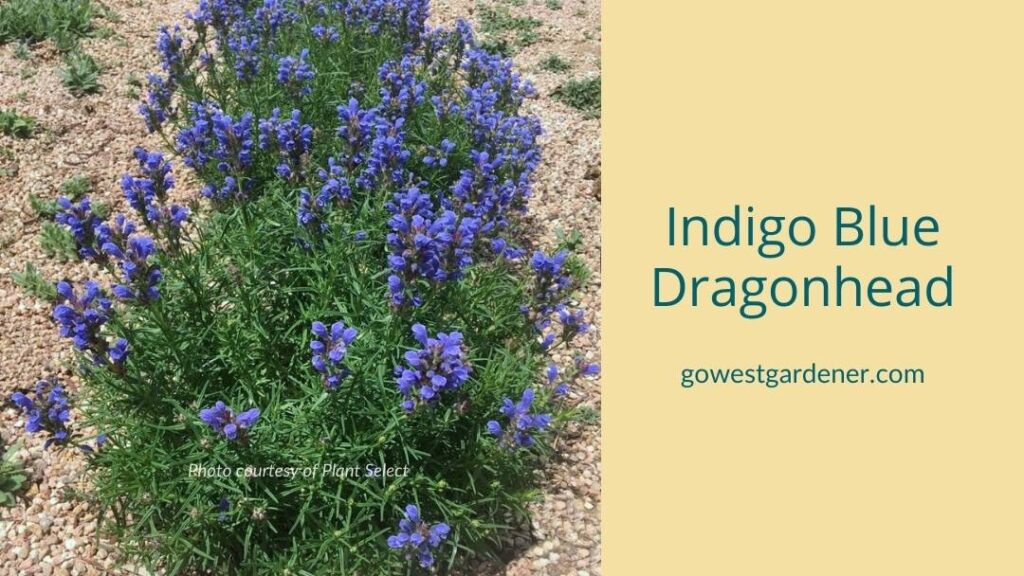

Indigo blue dragonhead (Dracocephalum ruyschiana)

Zones 3-8

Indigo blue dragonhead gets blue flowers in the early summer. This perennial has vibrant-green foliage with needle-like leaves. I think it looks pretty when it’s paired with waterwise perennials that have silver foliage.

Indigo blue dragonhead is drought-tolerant and easy going. You can plant it in a variety of soils. It’s happiest in sunny locations.

Cape forget-me-not (Anchusa capensis ‘Cape Forget-Me-Not’)

Zones 5-10

Cape forget-me-not grows in full sun and part shade. In sunny locations, it prefers a little more water.

This attractive perennial from South Africa starts blooming in April, and it can bloom into the fall if you keep deadheading it. Honey bees love the sky blue flowers.

This waterwise, blue flower can be a shorter-lived perennial. If you want it to continue in your garden, let some of the spent flowers go to seed. With that said… it easily reseeds, so if you don’t want a lot of new plants, be sure to deadhead the spent blooms.

Prairie salvia (Salvia azurea)

Zones 5-9

Prairie salvia is a regionally native plant that gets blue flowers on tall stems in mid- to late summer. It’s a prairie plant that attracts pollinators, like bumble bees and hummingbirds.

This waterwise perennial grows well in our tricky western soils, from clay to sand. It doesn’t need a lot of water, and it’s happiest in sunny gardens. If you plant it in rich garden soils (meaning your dirt has a lot of organic material in it), it can get floppy.

Prairie salvia looks lovely when it’s planted among ornamental grasses, like little bluestem, and goldenrods.

Blue Glow globe thistle (Echinops bannaticus ‘Blue Glow’)

Zones 3-8

Blue Glow globe thistle produces round flowers—blue globes—in the middle of summer. The round flowers create an interesting focal point in waterwise gardens, creating contrast with other plants. This perennial gets reasonably tall (up to four feet tall), so plant it in the middle or back of your garden. It thrives in sunny, hot and dry locations, and it can bloom for a long time.

This beauty attracts a range of pollinators, including honey bees and bumble bees. In my garden, I’ve seen hummingbirds visiting it as well.

When you see the word, “thistle,” you may think, “Eeek, is this the bad kind of thistle?” Blue Glow echinops isn’t the invasive type of thistle, but it can reseed. If you don’t want it taking over neighboring plants, deadhead it when it’s done blooming.

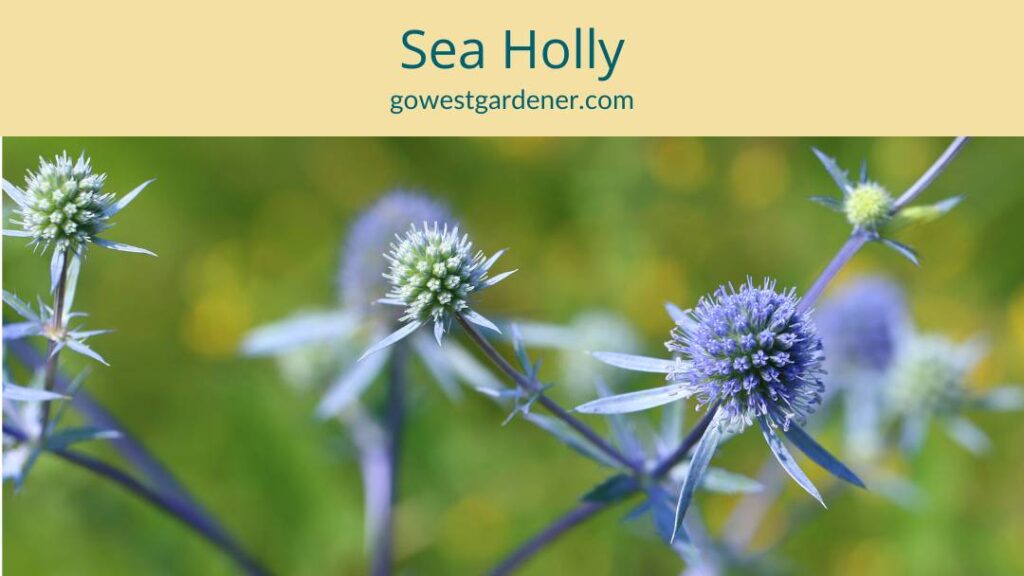

Blue Glitter sea holly (Eryngium planum ‘Blue Glitter’)

Zones 4-9

Another waterwise plant with interesting flowers!

Blue Glitter sea holly gets blue, spiny flowers on blue stems in the middle of summer. It thrives in sunny, dry locations. (You’ll find other sea holly plants on the market, but they aren’t always as drought tolerant as Blue Glitter.)

My neighbors ask me about this plant every summer. I’m partial to it because it looks unusual, and it’s a party for pollinators, including native bees, beneficial wasps and butterflies.

FALL BLOOMERS

Autumn Sapphire sage (Salvia reptans ‘P016S’)

Zones 5-10

There are a couple of waterwise, blue flowers that shine in the fall, including Autumn Sapphire sage. This drought-tolerant perennial adds a pop of color in September and October when other flowers have stopped blooming. Plus, it’s a source of nectar and pollen for late-season pollinators, including bees and butterflies.

Autumn Sapphire sage has willowy, green leaves. It looks lush and green in July and August, despite our heat in Colorado and Utah. Small, sapphire-blue flowers cover this plant in early fall. It can bloom until frost.

I think it’s pretty when it’s paired with hyssops (Agastache), western salvias and ornamental grasses.

Hardy plumbago (Ceratostigma plumbaginoides)

Zones 5-9

Hardy plumbago is another late-season bloomer. It gets bright blue flowers in the late summer and early fall in Colorado. Hardy plumbago is a groundcover, growing up to 8 inches tall and spreading about 18 inches wide.

Hardy plumbago will happily flower in the shade. Known as a “dry shade” plant in Colorado and Utah, hardy plumbago doesn’t need a lot of water in the shade. (You can plant it in the sun too, but it will be happier with more water in the sun.)

Another bonus… Hardy plumbago’s leaves turn a deep red color in the fall, adding an extra pop of color to your fall landscape. In the photo above, the leaves have started changing color.

Related topics that may interest you:

If this article was helpful to you, please share it!

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Sep 12, 2025 | Gardening for Pollinators, Gardening Tips and Tricks

Black-eyed Susan (officially, Rudbeckia — Rude-bek-ee-uh) is an easy-to-grow flower that can add big color to your western garden, particularly in the late summer.

But often, gardeners plant Black-Eyed Susan… and it doesn’t come back

If this happens to you, you may find yourself thinking: “Well, that article was a load of crap.” 🙂

Or worse, you may think: “I guess I just don’t have a green thumb.”

I’m here to tell you this isn’t the case! But there are helpful things to know about Black-Eyed Susan that don’t always get mentioned at the garden center.

So, in this article, you’re going to learn…

How to tell the difference between short-lived vs long-lived Black-Eyed Susans (“biennials” vs “perennials”)

I’m going to use a little garden lingo later in the article (bring on the Latin!), but I promise I’ll explain what it means.

Some types of Black-Eyed Susan are much shorter-lived than others.

So, what are some ways to know what you’re buying?

- Take a good look at the plant

- Look at the botanical name on your plant tag (the Latin jibber-jobber I’ll explain in a sec)

The plants below are Black Eyed Susan.

What do you notice?

In the Plant A photos, do you notice the hairy leaves and stems? When you touch them, they feel fuzzy.

If your Black-Eyed Susan is fuzzy, you likely have a shorter-lived plant

Fuzzy Black-Eyed Susan plants are known as Rubeckia hirta. They tend to be shorter-lived.

If you’re new to plant names: Rudbeckia describes a group of plants with similar traits. Hirta is like a descriptive adjective. It loosely translates to “hairy” or “rough” in Latin.

To keep things basic, plants with the botanical name, Rudbeckia hirta, include different types of hairy Black-Eyed Susan.

We’ll chat about WHY plants are hairy at another time. (Does this make your list of topics you NEVER thought you’d talk about today? “Hey, why are plants hairy?”) But for now, don’t let the hair distract you. The hair itself is not why the plant is shorter-lived. It just happens to be a clue you can use to assume you have a shorter-lived plant.

It also helps to look for the botanical name, Rudbeckia hirta, on the plant tag. Unfortunately, growers use ALL kinds of names on plant tags, so this isn’t always a sure thing.

The next question you may be wondering is,

“Okay, so how long do hairy Black-Eyed Susan plants live?”

Generally, Rudbeckia hirta are “biennials” or “short-lived perennials.”

They go through a 2- and sometimes 3-year life cycle, and then they’re done.

Depending on your garden center, you may find young, leafy Rudbeckia hirta in the “perennials” section of the store — the section with plants that come back.

But, Rudbeckia hirta can be sold in the “annuals” section of the store too. Annuals are the flowers that give you colorful flowers for one season, but typically don’t return next year.

(Because it’s never simple, oye!)

When the plant is in the annuals section, the garden center is likely selling it in its second of growth. Your plant is flowering, and it’s near the end of its life cycle.

You can just enjoy varieties like these for the summer and fall, and pull them out at the end of the growing season.

But if you have them in your flowerpots and you WANT to see if they’ll come back, you also can move them to the ground in the early fall to see if they’ll return next year.

Depending on where you live, these plants may survive a winter or spread through their seeds.

Even though Rudbeckia hirta plants tend to be short lived, they CAN make new plants from their seeds, so Black Eyed Susan may keep reappearing in your garden year after year.

Bonus! More plants!

(But reseeding is a topic for another day.)

Okay, back to our comparison photos.

What do you notice about Plant B?

Plant B has smooth stems and leaves.

It’s a different species of Black-Eyed Susan. Specifically, it’s the longer-lived type of Black-Eyed Susan known as Rudbeckia fulgida. Fulgida loosely translates to “shiny” or “glimmering.”

Think of it as a shiny-leafed Black-Eyed Susan.

Below, you’ll find some examples you may find at your garden center.

‘Goldsturm’ a is popular variety. It was the 1999 Perennial Plant of the Year — an award given to plants that are standouts from other varieties. This plant should return for many years.

‘Goldsturm’ is happier with moderate watering, so you may not want to plant it in a dry, hot garden.

Which Black-Eyed Susan is native?

A native plant is one that has existed naturally in an area for hundreds of years. It wasn’t introduced through European settlers.

Rudbeckia hirta — hairy Black-Eyed Susan — is native to the central United States. It is highly attractive to pollinators, and it’s a host plants for many butterflies (meaning they seek those plants out for their young).

So, if you’re interested in native plants for your garden and/or you want a pollinator-friendly garden, you may prefer growing Rudbeckia hirta.

Bring on the Black-Eyed Susan!

These aren’t the only species of Black-Eyed Susan, but they’re popular ones. And they’re a great place to start for your western garden.

The next time you’re at the garden center, look for Black-Eyed Susan plants. Touch the leaves and stems to see if they feel fuzzy.

If you feel hair, you’ll know what that clue is telling you: You likely have a shorter-lived plant.

Parting thoughts: This article is intended as an overview. It’s good to check the plant tag, or even better, read an online plant description from a grower for the specifics on the plant you’re buying, such as how long it should live, its plant hardiness zones, etc. There can be many nuances among individual plant varieties.

Related topics that may interest you:

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Sep 12, 2025 | Garden design Ideas, Gardening Tips and Tricks

You want your spring flowers to look pretty, but what’s the best way to design them?

How do you make the biggest impact?

Great questions!

In this week’s post, you’ll find 4 simple tips for spring bulb garden design. Use these tips when you plant your bulbs in the fall, so you can get a pretty look in the spring.

Plus, I’ve included a bonus tip on bulb planting… because gardening in the high-elevation West is an adventure, y’all!

For this article, let’s say you want to plant spring flowers in selective places in your yard.

For example, you want to plant them along a walkway or add pops of color through your garden.

We’ll assume you DON’T want to fill an entire garden bed with a mass planting of bulbs. (Your design approach will likely be different for a mass planting.)

I like to share upfront: Gardening is personal.

It’s your own form of artistic expression.

So, if you prefer to do something different than what I’m suggesting, do what makes you happy!

Okay, let’s jump into these tips on spring bulb garden design.

Design tip #1: You can create visual interest when you plant bulbs in small groups.

Translation: It looks really pretty!

For most plants, you dig a hole, and you place 1 plant in the hole.

But spring flowers can look lonely or out of place when you see a single flower only.

Instead, you can make a bigger impact with your spring flowers when you plant them in small clusters or groups.

And hey, we want some “wow” factor!

This means you’ll place a number of bulbs in a hole — rather than just 1 individual bulb per hole.

Design tip #2: Flowers look really good when they’re planted in odd numbers.

They look really good in sets of 3, 5, 7 or 9 plants.

This is known as the “rule of odds.”

Think of it as a helpful guideline, rather than a “you must do this” rule.

But it’s the same principle that’s used in many forms of art and design — from photography, to interior design.

Odd numbers create visual interest. They look good to our eye.

Why? Because:

- Odd numbers look natural.

- They feel more dynamic. (They aren’t too matchy-matchy to lose our interest.)

- They don’t compete for our attention, which can happen with even numbers.

- They give us repetition, but with variety.

So, what does this mean for your garden?

Spring flowers look great when you plant them:

- In an odd number of groupings

- With an odd number of flowers in each group

When you plant your bulbs, dig a wider hole. Place more than 1 bulb in the hole.

Here are common questions that come up about this:

- “What if I have an even number of bulbs?” If you’re buying a package of bulbs, you’ll often end up with an even number, like 12, 20 or 50 total bulbs. Do your best to achieve odd numbers where you can, but it’s 100% okay to plant an even number of bulbs in 1 or 2 holes.

- “What if I don’t have that many bulbs?” Try small groupings of 3 to 5 bulbs. They should still look good.

- “How far apart do you place the bulbs in the hole?” It varies by plant. Generally, you want to give the bulbs some space, rather than having them touching each other. With tulips, for example, you may want to space your bulbs 2″ to 5″ apart in the hole.

Design tip #3: Plant the same colors together for big pops of color.

Let’s say you’ve purchased several colors of spring flowers.

You can create vibrant pops of color when you group the same colors together.

This means you may want to plant 1 color per grouping.

For example, let’s pretend you bought bulbs for pink tulips and for white tulips:

- Group the pink tulips together.

- Put the white tulips in different clusters.

You can still plant the different clusters near each other for pretty variety!

And yes, there are times when mixing the bulbs together may make sense for you. For example:

- If you bought a bag of pre-mixed bulbs, those bulbs are likely designed to look great together. Mix away!

- If you’re doing a mass planting and filling an entire garden bed with bulbs, you may want to mix all the colors together. It depends on the look you’re going for.

Design tip #4: Consider planting your spring bulbs behind or among perennials.

Some spring flowers — like tulips — go through a not-so-pretty phase when they finish blooming. Their leaves get floppy and turn yellow.

It’s important to resist the urge to cut off those floppy, yellow leaves.

And this is where spring bulb design comes in handy!

Plant your bulbs behind or next to perennials. Perennials are the flower plants that return year after year.

When your perennials begin to grow in the spring, their foliage can help mask the fading leaves on your spring bulbs.

BONUS tip: Be careful planting bulbs in hot spots in your garden.

We’re gardening at elevation in Colorado, Utah and the intermountain west. This means that the sun is very intense on our flower plants — especially in certain parts of our yards.

Let’s say you want to plant your spring flowers along a sunny, south-facing or west-facing structure (like a wall, fence or building).

The temperatures can get hotter here than other parts of your yard.

In garden lingo, this is known as a “heat sink.”

Think of it like a little micro-climate in your yard.

Sometimes, this can create tough conditions for your flowers.

So, what does this have to do with your bulbs?

When you plant your bulbs in these hot spots, your bulbs may think it’s time to get the party started earlier in the spring.

The ground may warm up faster.

Your flowers may want to emerge too early.

They become vulnerable to freeze damage.

If your flowers are getting ready to bloom and the temperatures plummet for a few days, it can nip your flowers’ buds for that year.

Some years, you may not have an issue.

But other years?

You may need to babysit your plants.

I had purple allium planted along a sunny, south-facing fence.

We had a bad year of freeze damage. The allium had brown leaves and shriveled up buds. I realized I should have taken extra steps to protect them.

You’ll have less work if you avoid planting bulbs in these hot spots.

Related tips that may interest you:

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Sep 12, 2025 | Gardening Tips and Tricks, In-ground garden

What NOT to Plant in Fall Gardens

Early fall can be a good time to plant perennials in many places in the intermountain West. (Perennials are your flowers that return year after year.)

But as I’ve learned the hard way in my Colorado garden…

There are some flowers you may not want to plant in the fall in Colorado, Wyoming and similar western states.

Some plants need a little more time for their roots to get established before winter.

Here are a few examples.

Avoid planting “marginally hardy perennials” in the fall.

What’s a marginally hardy perennial?

It’s a plant that won’t come back if it gets too cold or if it can’t handle winter conditions where you live.

Usually, these plants are better off when they’re planted in the late spring or early summer. That way, their roots have ALL summer to get established in the ground.

This gives them a better chance of surviving their first winter.

Here’s a simple trick to tell if a perennial is marginally cold hardy >>

The pink flower pictured above is known as Gaura or Wandflower (Gaura lindheimeri). I LOVE this flower plant, but it’s marginally hardy in my garden along the Front Range of Colorado.

Some years it comes back. Some years it doesn’t, and I have to replace it.

Because I know it’s marginally hardy in my garden, I wait until spring to plant it. I don’t plant it in the fall. That way, it has as much time as possible to get established before winter.

Native western salvias often do better with spring planting.

Native western salvias occur naturally in Texas, New Mexico and the Southwest. They go by botanical names like Salvia greggii and Salvia darcyi.

You may see popular ones at the garden center called Furman’s Red Sage and Wild Thing Sage.

Native western salvias thrive in hot and dry climates, so they grow well in our summers at our lower elevations.

These showy flowers are drought tolerant, long blooming and a favorite among hummingbirds.

So many reasons to love them!

But native salvias can be fickle in our winters.

It’s best to plant them in the spring or early summer (like May or June), rather than in the fall.

That way, their roots can get a running head start into autumn and winter.

In general, don’t plant evergreen trees in the fall. Spring is a better time.

While we’re on the subject of “what not to plant in the fall” in states like Colorado and Wyoming, add evergreen trees to your list too.

Evergreens (aka, “conifers”) are your trees that have needles. They don’t go dormant in the winter. This means they don’t go into hibernation mode like your trees that lose their leaves. They are awake and “ever green” through the winter.

Evergreen trees need to be well watered over the winter.

They’re also vulnerable to our tough winter conditions — like our drying winter winds and our big temperature swings — because they aren’t dormant.

It’s best to plant your evergreen trees in the spring, so their roots have more time to get established before winter.

Keep in mind, these are guidelines, rather than rules.

We may get a mild winter, and your plant babies may be fine.

But if you’d rather not risk it, then just wait until late spring to plant the flowers and trees in this article.

Related tips that may interest you:

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Sep 12, 2025 | Gardening Tips and Tricks

Looking for a fun fall project that will make your front porch look GOOD?

Use a pumpkin as a planter. You’ll create a cute autumn flowerpot that has your neighbors saying, “Wow!”

I created pumpkin planters with a friend last fall. This project is quick and easy. (Yesss!) And I got great feedback from my neighbors.

Scroll on to get the scoop on how to use a pumpkin as a planter.

What you need to make a pumpkin planter…

The basic things you need are:

- Large pumpkins

- Flowers in pots (you’ll keep your flowers in the nursery pots rather than planting them directly in the pumpkin)

- Pumpkin carving tools

- OPTIONAL: An anti-desiccant spray (this is supposed to help the pumpkin from drying out)

Alright, let’s jump into the steps!

Pick a big pumpkin.

Size matters here. Look for a big pumpkin.

I took an empty flowerpot with me to the store, so I could get a sense for how big of a pumpkin I needed.

I’m not great at spatial planning, so this helped me a lot.

Wash your pumpkin.

Clean the outside of your pumpkin with soap and water.

This will help it look like a shiny, new penny and keep your hands clean.

Create the hole for the flowerpot.

Trace a hole on your pumpkin that’s slightly bigger than the size of your flowerpot.

Clean out the inside of the pumpkin.

Make sure the hole is big enough to easily remove the flowerpot for watering. As you can see in the photo below, I needed to slightly expand the hole.

It’s important to be able to remove the flowerpot.

When you water your flowers, you’re going to pull the flowerpot out of the pumpkin. That way, you don’t have water seeping into the bottom of the pumpkin.

When you’re done watering and the water has stopped dripping, you’ll put the flowerpot back in the pumpkin.

If there’s any chance you’ll have water dripping at the bottom, you may want to carve a drainage hole in the bottom of the pumpkin too.

Get creative with where you carve the flowerpot hole.

You don’t have to cut the hole for the flowerpot where the stem of the pumpkin is.

My friend found a cool pumpkin that looked better on its side, as you can see below.

Optional: Once the pumpkin is cleaned out, spray the interior with an anti-desiccant.

An anti-desiccant spray is supposed to help keep the pumpkin from drying out. I found the spray at a local garden center last fall. You also can order it on Amazon.

Follow the instructions on the bottle for how long to let it dry.

Full disclosure: I didn’t find that the anti-desiccant made much of a difference, so I’m not going to use it this year.

You could stop here, and you’d have a really cute pumpkin planter.

Or, you can go a few steps further…

Turn your pumpkin planter into a Jack O’Planter.

I felt like my pumpkin needed a little “oomph,” so I decided to carve it.

You could carve anything you want into your pumpkin: a funny face, a pretty pattern, the brand logo for your business…

In my case, I started with a leaf.

Here’s how my pumpkin planter turned out.

I was excited with how it came together!

How do you get your flowerpot to sit at the right height in the pumpkin?

You may need to put something inside the pumpkin for the flowerpot to sit on.

In my case, I turned an old plastic cup upside down inside the pumpkin. Then, I set the flowerpot on top of it.

This helped the flowers to sit at the right height.

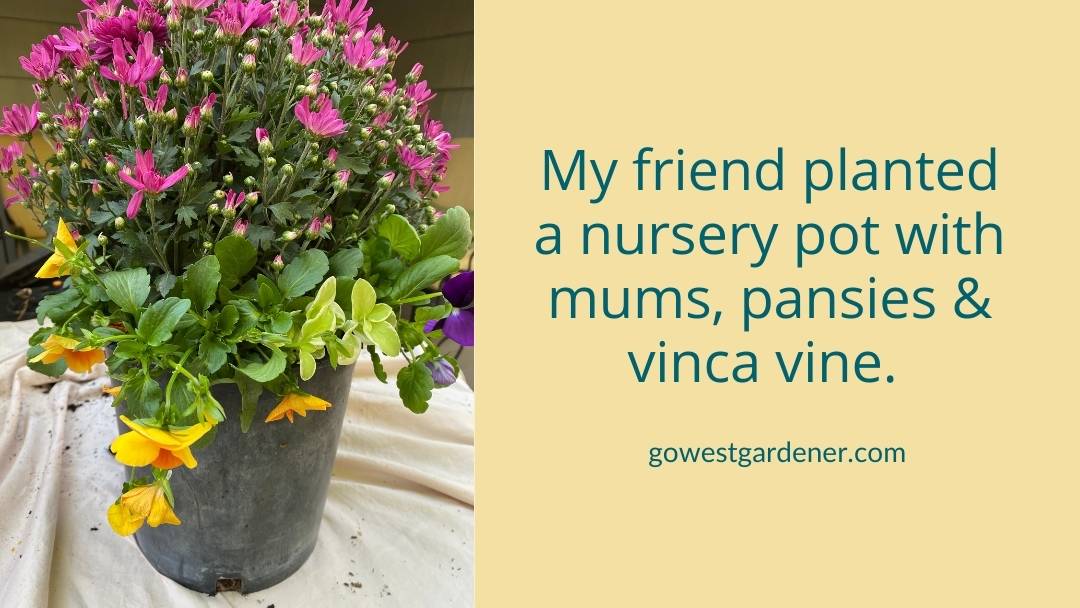

Plant a pretty mix of fall flowers.

If you want to use a pumpkin as a planter, you also could include a mix of fall flowers.

(Go big, right?)

My friend filled an empty nursery pot with potting soil and packed in several types of fall flowers, like mums and pansies.

Then, she put that flowerpot inside her pumpkin planter.

Here’s a look at both of our pumpkin planters.

Cute, right?

What we may tweak for this autumn…

My friend and I may experiment with adding in other types of pumpkins this year. I have a ceramic Jack O’Lantern pumpkin. My friend has a craft pumpkin from a craft store.

We’re going to see if these options help our fall displays last longer.

At the very least, the squirrels should be less interested in the pumpkins.

But I’m also going to carve real pumpkins again and use them as planters.

It was fun!

If you make a pumpkin planter, share it on Instagram or Facebook and tag @gowestgardener. I’d love to see what you create.

Related tips that my interest you

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Jun 20, 2025 | Gardening for Pollinators, Gardening Tips and Tricks

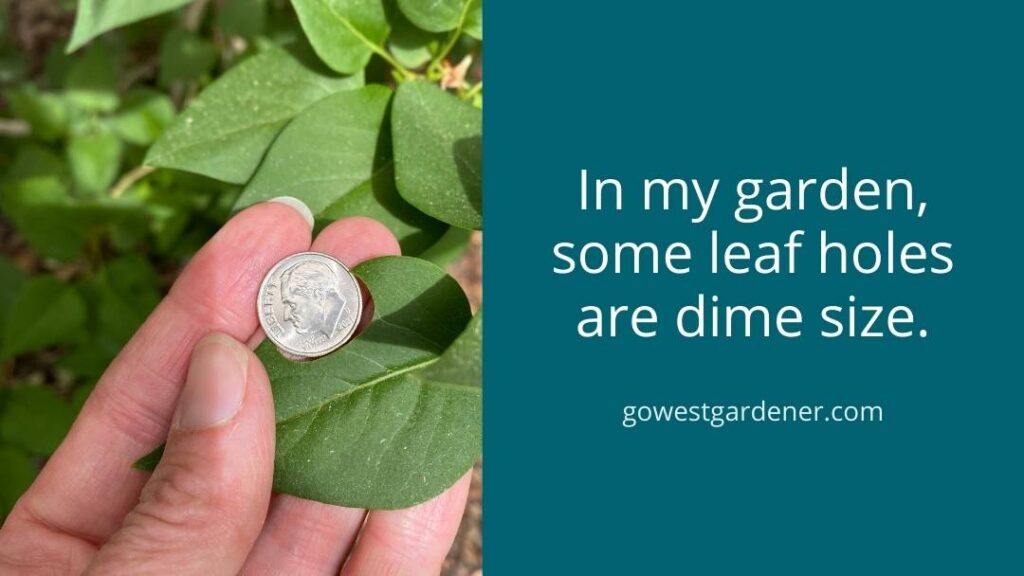

Let’s say you’ve noticed some strange, round holes in your plant leaves. These circular holes have fairly smooth edges. It almost looks like someone took an office hole punch and punched circles along the edges of your leaves.

What’s making these round holes in your plant leaves?

Is it Japanese beetles??

Nope, Japanese beetle damage looks different.

It’s more likely you have leafcutter bees—a native bee and beneficial insect in Colorado. They’re important pollinators for wildflowers and some fruits and veggies.

(Cool!)

Leafcutter bees aren’t eating your leaves. Rather, they’re cutting circular pieces to use in the nests they’re building for their babies. They’ll insert the leaf piece into a hollow tunnel, along with nectar and pollen. Then, the mama bee lays an egg and seals it off. Her bee nursery is ready to go.

What plants do leafcutter bees like?

Almost any plant with broad, thin leaves is fair game. In my garden, the leafcutter bees love cutting round holes in the leaves of my lilac bushes and a flower plant called Golden Candles (Thermopsis lupinoides). In Colorado, leafcutter bees often are fond of rose bushes too.

I’ve noticed circles and semi-circles that are dime size, but many of the holes are smaller.

So, should you be worried about the round holes in your leaves?

Typically, no. The damage from leafcutter bees is only aesthetic.

Insecticides will not prevent bees from cutting holes, according to the Colorado State University (CSU) Extension. So, save yourself money and a trip to the hardware store. Skip the insect sprays and powders.

(This will keep your garden ecosystem healthier too.)

In most cases, you don’t need to do anything…

Except maybe point out the leaves to your friends, so they can see that your garden is a favorite among pollinators.

If you have a plant that the leafcutter bees have become REALLY fond of, the CSU Extension suggests covering the plant with loose netting or cheese cloth if you want to deter the bees from making holes. Put up the netting when you first notice damage.

Just keep in mind the damage is only aesthetic. You’ve got busy pollinators at work in your landscape. 🙂

Now, if the holes on your leaf edges are jagged and look like notches…

Then, you likely have a different insect.

Root weevils are a type of beetle. At night, the adults chew jagged notches along the edges of plant leaves. You can find root weevil leaf damage on lilacs, peonies and privets, as well as other plants.

To me, the edge of a leaf with root weevil damage looks like the edge of a key. It’s more jagged than the symmetrical, round holes from a leafcutter bee. Can you see the difference below?

If you want to learn more about root weevils (and see more photos of their leaf damage), check out this root weevil summary from the CSU Extension.

Related topics that may interest you:

by Ann at Go West Gardener | Updated: Sep 12, 2025 | Gardening Tips and Tricks, In-ground garden, Waterwise Gardening in the Intermountain West, Western Container Gardening With Flowers

Many years ago, I cheered on a friend as he ran a local marathon. As my friend began running, he looked like he belonged in a Nike ad: Strong. Healthy. Determined. Just do it, baby!

And he set a great pace until about mile 16 …

… when heat and exhaustion caught him like a cat chasing a mouse. Life decisions were questioned. (Was a burrito really the best decision for breakfast?) He was doing the best he could, but he was digging deep.

I find myself thinking about mile 16 as we slog through heat waves in our western gardens.

Temps are blazing. Weeds are thriving. Critters, like Japanese beetles, are munching. And munching. And munching.

It can feel a little exhausting. Garden decisions are questioned: Was it really the best idea to impulse-buy flowers in the last 2 weeks? (Asking for a friend. Ahem.)

Heat waves are an ideal time to talk about how to garden smarter, not harder.

If you find yourself gardening in the heat, here are 5 ways to keep the beauty coming with less effort.

1) Make sure your flower garden has 1-2″ of mulch.

Mulch is your friend when you’re gardening in the heat. It keeps your plants’ roots cooler. (Happier plants!) It keeps your plants hydrated. (Less watering!) It helps suppress weeds. (Less work!)

If you aren’t familiar with mulch, it’s a material you put on top of the ground—like small wood chips or “squeegee,” which is a smaller form of pea gravel.

You can even put mulch in a flowerpot if you want.

I use a few different materials for mulch, depending on the plants. Some of my gardens have mini-bark (small wood chips). Some have “soil pep” (a very fine wood mulch). I like these smaller wood mulches because they break down more easily than big, chunky wood mulch, adding organic material to my garden beds. They’re less likely to soak up water like big, chunky wood mulch. I also think they look better, but that’s just personal preference.

In my more xeric gardens (the low-water gardens), I use squeegee as a mulch. It drains well, and it doesn’t add organic material to the ground. Many low-water plants like “leaner” soil, meaning it isn’t rich in organic material.

2) Snap a few pics of your flowers on your phone.

Take note of which flowers look like champs in the heat, which plants are limping along, and which flowers are guzzling water like a 6-year-old chugging juice boxes.

At some point, you may wish to replace the strugglers and water guzzlers with flowers that thrive in our western heat and drought. That way, you can spend your time sipping chilled beverages and dazzling your friends with how fab your garden looks.

You can find western flower ideas here.

3) Focus your energy on newly planted flowers.

Have you popped any plants in the ground or in your flowerpots in the last 4 weeks? Those plant babies need more attention in the heat. Heck, even low-water plants need frequent watering their first season, so they can establish healthy roots.

For your in-ground plants, I’ve found that rain umbrellas make wonderful sun shields for new plants in extreme heat. Just make sure it isn’t windy. (Learned that one the hard way!)

You also can prop up shade cloth, which you can find at garden supply companies.

Another tip… Plant small, landscape flags next to your new plants during their first month. That way, you’re less likely to overlook them or forget to water them, especially if they’re tucked in among bigger plants.

When temps are blazing in months like July, it’s a good idea to check newly planted flowers every day (for the first 4 weeks or so) to see if they need water.

And consider trimming off the flower blooms on your newly planted perennials (the plants that come back every year). Snip, snip!

You may be thinking, “Wait, whaaaaat??”

I know that sounds a little crazy. You probably bought the plant BECAUSE OF the pretty blooms. But cutting off the flowers can allow your new plants to focus their energy on establishing good root systems in the heat.

4) Be smart with your flowerpots.

If possible, give your flowerpots a good soak in the morning by 10 am. Watering in the morning reduces evaporation, and it helps keep your flowers hydrated through the day.

Some flowers in your pots may wilt from heat, rather than just from lack of water. (I’m looking at you, Sweet Potato Vine.) Before you water, make sure the soil (dirt) in your flowerpots actually needs water, so you don’t overwater your flowers by accident.

You may want to move any flowerpots that are struggling in the heat to a shadier spot for a few days, if you can.

5) Find efficient ways to water your garden.

For example, check out drip irrigation. Drip lines are thin, little hoses that run near your plants’ roots. Drip systems are 90% efficient, compared to sprinkler systems which are only 50%-70% efficient, says the Colorado State University Extension.

Do you have clay soil—dense, sticky dirt that’s common in many parts of the intermountain west?

If yes, it helps to get in the habit of watering your established plants deeply and infrequently, instead of giving them quick, daily splashes of water. This encourages your plants to grow deeper roots, so their roots can find water in the ground. (Read: Less work for you.) Use your best judgment, of course. If your plants need water, then water them.

Stay strong! Stay cool! You’ve got this!

Related tips that may interest you: